eBusiness Weekly

Chris Chenga

Supposedly, a new dispensation means developing friendlier ties between the UK and Zimbabwe. Any benevolent observer would not haste to cast doubt on the accumulating goodwill as resembled by the diplomatic visits and portraits amongst representatives over the last two months.

However, a responsibly conservative observer would moderate the excitable expectations that may lead to economic stakeholders growing discontent in due course, if actual tangibles may not be derived from this goodwill as soon as stakeholders would hope for.

Excitable expectations would be in the nature of seeing visible business activity, whether in the form of financial inflows across capital markets, cargo shipments between countries, or legally binding covenants between economic entities as recorded by the Zimbabwe Investment Authority.

There is a lot of hard work and graft yet to be done until such business activity is to be seen, especially in the eyes of local stakeholders hoping to emerge from a prolonged period where the volume and propensity of western business in their portfolios has been close to nil.

Indeed these excitable expectations may be held by British economic stakeholders too, particularly those in the manufacturing of goods. In the UK, the overall economy has not been flourishing to sustain positive sentiment amongst UK companies. Slow macro-economic growth due to lower productivity of goods, has led to slumping real wages and welfare amongst its workers.

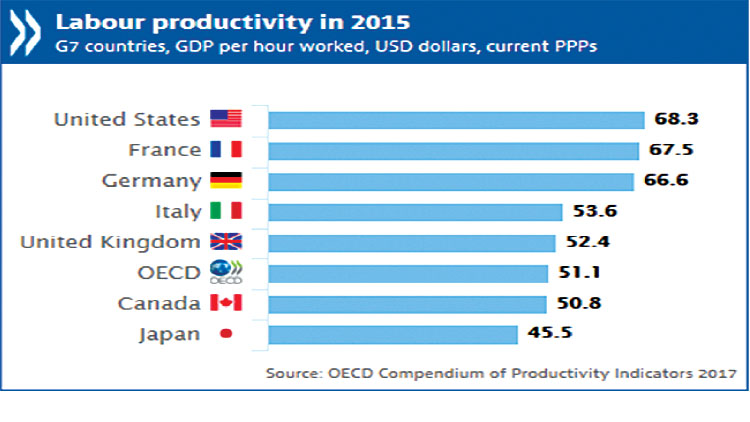

According to OECD productivity indicators, UK productivity is barely average in the European Union and lower than its main trade partners. With UK goods continuously becoming less competitive to its developed economy peers both in the East and the West, it faces a growing deficit in trade balance.

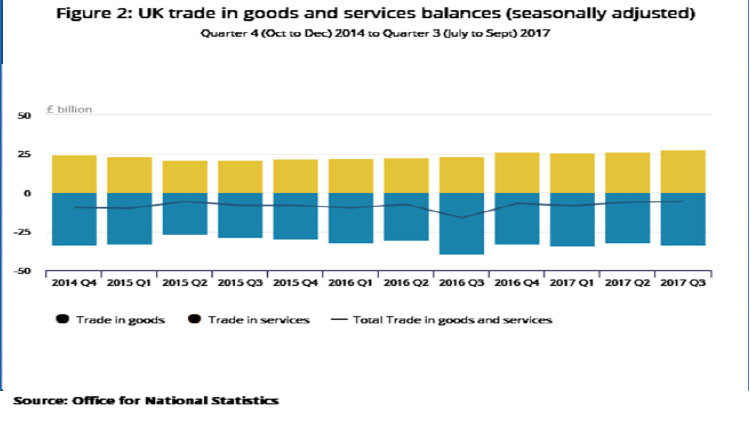

A resilient services sector has remained UK’s economic edge, sustaining a sectorial trade surplus. In the third quarter of 2017, UK service surplus grew to a record £27,7 billion led by business and financial services.

Unfortunately, the uncertainties of an arduous Brexit process are piling anxiety towards this services sector, as it is greatly exposed due to potential changes in migrant and skilled worker legislation — a core motivator of the Brexit vote itself.

Indeed, what this means is that the UK would significantly be aided by harnessing new frontiers that could boost its manufacturing productivity, especially through raw material and component sourcing to make its goods more competitive to its trade partners. This should be the theme of Zimbabwe’s new relations with the UK.

From a Zimbabwean perspective, getting inclined to the British economic outlook is imperative in terms of identifying potential offerings in bi-lateral relations. A lot of due diligence on the structural make up and trends of the UK economy is necessary in designing complimentary proposals that suggest value to the UK.

Moreover, understanding the current UK political rhetoric and tone such as austerity and budget conservatism informs a better approach strategy of engagement. While pursuing contentious cuts in its public spending to its own citizens, the UK has become more critical of its aid investment into developing nations; thus, a lazy dependency approach of bygone years would be met with great disinterest.

What we must appreciate — and is a lesson that the UK is going through at the moment with Brexit — is that structuring mutually beneficial economic relations takes exhaustive due diligence and time before anything concrete is in place.

Theresa May’s administration has reportedly been looking to hire up to 300 trade experts to comprehend potential trade implications during the Brexit process. Granted, that particular process overshadows bilateral discourse with a $14 billion Zimbabwean economy, it suggests the magnitude of diligence it takes to structure new arrangements between countries. And as Zimbabwe has practically been idle in business exchange with the West, perhaps any amount of new relations would be of Brexit magnitude to the good men and women of our civil service.

Considerations between UK and Zimbabwe must delve into the potential volume of goods to be exchanged between countries, the terms of trade of these respective goods, the infrastructure and platforms such as borders and travel routes in which business will be carried out, and that the bilateral accords of cooperation signed between UK and Zimbabwe are facilitative of efficient execution of all these aforementioned considerations as sometimes paperwork intervenes actual business activity. This is serious diligence for multiple professions, and cuts across many institutions of governance.

A helpful point of reference in strategising relations is to stay informed on the UK’s continuous relations with other developing nations. According to Reuters this week, Britain’s export finance agency decided to add Nigeria’s currency, the Naira, to its list of “pre-approved currencies”, allowing it to provide financing for transactions with Nigerian businesses denominated in that currency.

The UK will provide up to 85 percent of funding for projects containing at least 20 percent British content. This means that Nigerian firms taking out a loan in the local currency can benefit from a UK government-backed guarantee.

This is a huge development. It can be perceived as the UK opening up export markets for its goods, but it can also be interpreted as the UK increasing its flexibility in facilitating trade infrastructure between itself and developing nations.

Investment and trade between developed and developing nations has typically been made difficult by soft infrastructure barriers, such as correspondent banks and monetary facilities; let alone when a country is under sanctions.

Zimbabwe has lost more than a hundred correspondent banks within the last several years, affecting our investment and business connectivity with developed economies. Soft infrastructure has been a risk factor for companies and investors in the UK in their consideration to do business with developing economies.

New attitudes by the UK to take ownership in risk mitigation, and compromising on historically high developed world soft infrastructure standards, helps nations like Zimbabwe connect more easily with counterparties in the UK.

This can be interpreted with the aforementioned need for the UK to harness new frontiers that could boost its manufacturing productivity, especially through raw material and component sourcing to make its goods more competitive. We should take advantage of this.

Real cases exist in sectors such as agriculture. Particularly, export of horticulture to the UK has been deterred by poor monetary soft infrastructure, with UK markets pleading too high a risk proposition buying from Zimbabwe.

Manufacturing components traditionally sourced from Zimbabwe lost their business appeal over time as incompatible soft infrastructure made raw material and component suppliers lose out on their place in UK manufacturing value chains. Hopefully, UK and Zimbabwean companies can do thorough value chain analyses and potentially find synergies that make Zimbabwean commodities and components make UK manufacturing more competitive.

Also, from the UK’s multilateral benchmarks, we can estimate reasonably competitive thresholds of our own where Zimbabwean companies can target. For example a 20 percent benchmark in UK components enforced by the UK government opens up to 80 percent counterparty potential within the value chain. This means that Zimbabwean companies can compete for up to 80 percent component and raw material supply. With such a high threshold of opportunity, value adding processes are a reality for local manufacturing.

If Zimbabwe and UK are serious about doing business these are just a few narratives and developments we should be reading about. These should be the themes of press releases from both governments. But we must always be cognizant, relations between Zimbabwe and the UK disintegrated over a series of events, but the main focus of disagreement was a land reform process.

Perhaps it is good that re-engagement is taking place now, whilst many within incumbency were present and actual actors within the matters of principal dispute; as opposed to an entirely new generation nurtured on impressionable politicized interpretations of whatever disagreements took place. Over the years, much of the stand-off between the UK and Zimbabwe has been politicized and adrift of the real disputes in terms of counter-party obligations as promised in covenants between our governments.

Indeed as the favourable narrative goes, Zimbabwe may have been considered the economic powerhouse of Southern Africa, but during that gilded era, prosperity still resembled unattended socio-political disparities from Zimbabwe’s colonial past. This fact should be present in both counter-parties as they work to create a future where Zimbabwe is truly an equitable economic powerhouse with resolved disputes.