eBusiness Weekly

Politicians are unmindful of business and market fundamentals

Chris Chenga

There is a contrast in the level of business interest when multilateral conferences take place in different global regions. Consider the business interest when, for instance, G20 nations converge for annual summits. Among other represented countries, businesses and investors from the likes of Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Japan pay close attention to proceedings.

Recurring themes such as sustainable development, socio-economic harmony and cross-regional integration all feature on the agenda of a G20 summit.

But, what makes a G20 summit stand out is that conference focus, though accommodating discourse for these recurring themes, places serious emphasis on issues of significance derived from business and market concerns!

The retained interest in these multilateral conferences is because business and markets are assured that deliberations will definitely exhaust matters to do with immediate business going concern and market well-being.

There is a clear disparity between the interest levels in developed nations’ conferences and conferences of developing nations. For instance, when the G7 summit (distinct from G20) took place in May, key issues were to focus on how climate change, trade agreements, and security, would have implications on each member nation’s respective business agency and market fundamentals. Consider how security matters were discussed within a context of potential disruption to key sea ports for cargo movement with specific companies in mind, or how climate change policy would impact identifiable industrial margins and cost variables for specific companies.

It would be concise to say that G7 politicians met to discuss business, and the well-being of the money that finances each nation’s respective capital markets!

This is not the case with African multilateral conferences. Indeed, multilateral conferences to do with developing nations, Sub Saharan Africa specifically, are more diverged between political representation and business consequence.

Our business and market attitudes reflect this diverged interest. Evidence to this point starts in business media coverage. When COMESA, ECOWAS, or SADC summits take place, these events are not really front page fabric!

This is because the consumers of business media, who are business agents and market investors, do not feel an immediate existential interest in summit deliberations.

Hence, they do not pay attention. The summits are not really of serious consequence. Conference agendas and communiques are not striking matters that affect certainty, competitiveness, and profitability of business and markets.

This matter can be perceived from two narratives. Firstly, perhaps politicians are unmindful of real factors that affect business and markets. Secondly, there is a space between politicians and business that requires to be trimmed with both groupings understanding their mutual interests. To illustrate how politicians are unmindful of real factors affecting business and markets, one can suggest topics that should have been on the agenda of recent summits across Sub Sahara Africa.

Commodity dependence

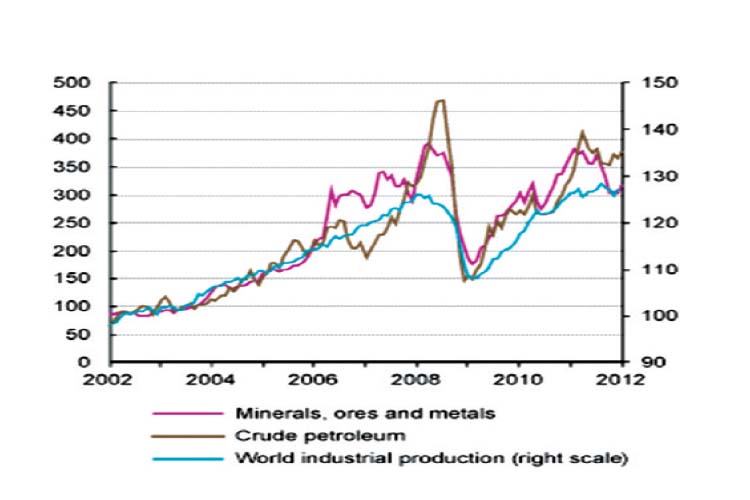

Commodity dependence should have featured high on priorities. Angola, DRC, Zambia, Zimbabwe are all greatly dependent on global commodity demand and prices.

As neither of these countries has discretion on commodity demand or prices, this means that national budgets are leveraged on variables that our governments have no control over. As a result fiscal and monetary policy for most African countries starts at a disadvantage on business and markets.

For instance, according to the IMF’s Article 4 report on Angola, the oil price shock that started in mid-2014 has substantially reduced fiscal revenue and exports. Currently Angola, which depends on crude shipments for 97 percent of its exports, requires oil prices to shoot up to $82 Angola to balance its budget this year according to estimates by Fitch Ratings. Oil is presently at $52.

Zambia’s exports are 85 percent copper receipts, and capital inflows of FDI are 80% into copper industry. Since copper prices fell in 2014, Zambia has been chasing up accumulated debts, influencing its fiscal and monetary policy.

Fluctuations in commodity prices disrupt national revenues and budgets

Source: UN Conference on Trade and Development

Evidently, commodity dependence should be a high factor which African politicians need to discuss for the comfort of business and markets. As volatile mineral prices are considered external factors, summit deliberations should be on strategies to sustain commodity revenues; perhaps instruments such as flexible mining royalties, or clear fiscal regimes that smooth price volatility on revenues.

Consider that in Nigeria, a three month fall in oil prices in 2014 resulted in an annual fall of the current account by 69,3 percent (from N$3,14 trillion in 2013 to N$964,6bn in 2014).

That means more trillions of capital flows were lost in just a quarter. The implication on tax revenue and expenditures is too significant. Fiscal and monetary management should function with an objective purpose of business and market certainty. Fundamentally, the impact of commodity dependence on business and markets is a subject matter demanding serious summit deliberation and focus.

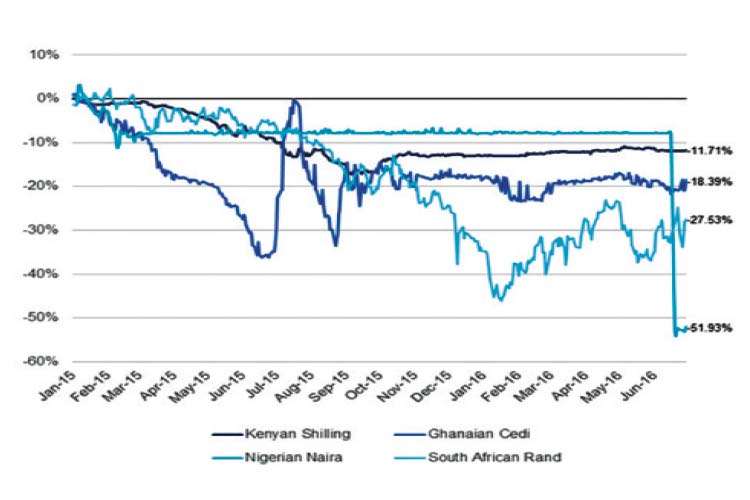

Currency volatility

Another topic for serious consideration is that of currency volatility. Very few, if any, African currencies sustain a normalcy for business and markets to hope for consistent growth and prosperity. Consider that most baskets of African currencies averaged annual volatility of 25 percent; meaning that floating exchange rates to currencies such as the USD, Euro, or Sterling moved more than 25 percent within a year.

African currencies have been volatile in short time frames

Source: Brookings Institute

Currencies bother our continent more that it does any other region in the globe. Furthermore, we lack comparable means to attend to currency difficulties. For example, 14 African countries have been using the CFA franc that is pegged to the euro, limiting any fiscal and monetary autonomy. This greatly diminishes the fiscal and monetary capacity of governments to be responsive to the needs of local business and markets. Central banks struggle then to control inflation and price variables that impact business.

Currency is also bothersome in terms of its availability. Investment and growth in Africa is largely dependent on the availability of foreign currency. Without adequate foreign currency reserves, business competitiveness suffers greatly.

Thus, due to numerous developing nation currency fragilities, our business and markets often find themselves in contest for these scarce foreign currency reserves with our governments. Interaction with global stakeholders is often rough without enough forex to transact with suppliers or counterparties. An immediate example is Zimbabwe’s present circumstance, but perhaps surprisingly to some, dynamics in Zimbabwe are also taking place in several African countries as well. Angola, Mozambique and Ethiopia are restricting access to business and markets in priority to governmental foreign currency reserves.

A greater threat to business and markets is that of currency speculators and market manipulators. This is more significant to our capital markets which require easy flow of money.

Sure, solid structural regulation of markets is imperative, but currency volatility frequently exposes our markets to speculators and manipulators.

Of course, raising matters on currency volatility does not generically imply suggesting monetary unions, currency boards, or continental monetary parity. However, business and markets require thorough deliberation by politicians on near term resolutions in as far as how governments shall manage economies as they relate to currency. These are immediate concerns for business and markets!

Patents, intellectual property, and technology transfer

In a world of increasingly fast paced globalization, it is correct that politicians speak on regional integration and cross border value chains. However, without business enterprises being preceded with favourable patent, intellectual property and technology transfer legislation, political talk is merely abstract while our businesses continue to lose market share to global competitors.

Deliberations on patents, IP and technology transfer are yet to bring to the forefront the concerns of developing nation businesses. The disparity between us and developed nation competitors widens.

According to a Citigroup report released in 2016, roughly 60 to 70 percent of retail banking employees are currently doing manual processing driven jobs. This implies inefficiency, and a technological deficit to work tasks.

In the last 15 years, labour intensity of manufacturing a dollar of output amongst developed economies now costs 11 cents less. In this same period, manufacturing nominal output shot up more than 54 percent.

This means that productivity output is significantly increasing at the same time manufacturing processes are finding capital intensive alternatives to labour. According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), slow technology transfer has increasingly made developing nation enterprises uncompetitive to developed nation peers.

Unfortunately, as global value chains intertwine, local businesses are pushed out of value chains because their technology does not compete in terms of efficiency and effectiveness.

The aforementioned topics are some of the most significant topics to affect business and markets in Africa over the last decade. All indications are that these topics unattended will continue to be deterrents to the growth and prosperity of our business and markets. Yet, summit and conference communiques make no reference to these matters of interest to business.

Lastly, the space between politicians and business needs to be trimmed to an extent where both groupings realize their mutual interests. Politicians and business should be cohesive in their interests. There is a long held misconception that the language of business should be distinct from the language of politics, or vice versa.

This is untrue! Matters to do with employment, improved labour welfare, socio-economic transformation are all derivatives of thriving business and markets. When politicians of developed economies meet, they must carry the word of business and markets.